The Fame Trap

The Rise of Psychological Monocultures in an Age of Visibility

Over the past decade, the world of psychology has moved far beyond the therapy room. Hundreds of thousands of people turn to online platforms, podcasts, books, and social media for psychological insight and emotional support. This has helped to make ideas once confined to academic journals or clinical spaces widely available to the public.

We have also seen individual psychologists and therapists rise to near “rock star” celebrity status. Their messages, as well as their personal brands and companies, have become powerful forces in shaping how we talk about trauma, vulnerability, healing, mindfulness, and relationships.

There’s no doubt that this shift has made psychological knowledge more accessible than ever. Whilst this is largely positive, I reflect here on the unintended consequences of this sudden high visibility and influence of a few influencers and the conditions that are needed to cultivate healthy systems of knowledge generation. How do we navigate a diverse psychological field in an era dominated by an attention economy and celebrity culture that is opening up and narrowing down diversity at the same time?

As we know from Jungian psychology, every creative force casts a shadow, not as a moral failing but as an inevitable companion to all human endeavours. Shadow is whatever remains structurally out of view. In the following, I want to shine a light on the part of the picture that often lies beyond the spotlight.

Feeding a collective hunger

In a fragmented culture, where loneliness has reached the level of a public-health crisis and where decades of individualism have eroded the social fabric, there is a growing hunger for community, meaning, belonging, and a shared language that gives form to inner experiences. People clearly long for cultural containers that acknowledge the depth of human struggle rather than pathologising it.

The scale of this hunger reveals how profoundly under-resourced our public institutions are when it comes to our emotional, spiritual, and psychological life. These collective needs are not being met in politics, education, healthcare, or the workplace, leaving millions of people searching for a place where their longings can be taken seriously.

In this vacuum, a small number of platforms have built global infrastructures capable of carrying psychological and contemplative knowledge at a scale that would have been unthinkable a generation ago. Their courses reach hundreds of thousands of people worldwide. Their membership communities span continents. Their programmes have shaped the language many people now use for trauma, relationality, and healing.

Equally, some individuals have risen to personal fame through their attuned creation of accessible entry points into material that, for decades, remained in specialist clinics, local communities, or small workshops. They have democratised psychological knowledge and built technological, pedagogical, relational infrastructures that allow hundreds of thousands of people to make meaning of challenging life experiences. They have created forms of psychological education that meet people where they are: at home with children, in full-time jobs, in situations with little access to therapeutic care, in moments of crisis when no other support is available. This has provided coherence, language, and companionship to people who would otherwise have been navigating complexity alone.

These developments have expanded our collective vocabulary for trauma, inner multiplicity, attachment, systemic wounds, grief, and transformation. These offerings have helped millions make sense of themselves and each other in a time when confusion, fragmentation, and fear easily take over. And crucially, they have done this with a seriousness of purpose. They have laid the ground for a significant shift in attitude where psychological maturity, presence, and relational skill are beginning to be recognised as essential capacities for this era. These are spaces of real learning at a scale that has genuinely shifted the psychological outlook of Western culture.

Yet, as with any period of accelerated growth, we must remain attentive to the systemic dynamics that inevitably accompany such success stories. In the following, I will explore the dynamics of the broader conditions we are co-creating, reflect on their unintended implications, and put forward some reflections of what a diverse and resilient ecosystem of psychological work might require in order to avoid the consolidation of monocultures.

Monocultures

If we take ecology seriously, then we have to recognise the signs that the current psychological landscape has slipped into the early stages of a monoculture. The problem is not the presence of large organisms. Healthy ecosystems need keystone species. The problem arises when the conditions become so skewed that the largest species expand without limit, and the smaller species that keep the soil alive can no longer survive.

In ecology, monocultures arise where conditions amplify a few highly efficient species that get over-nourished, expand rapidly, and outcompete everything else. These become the dominant life-form not because it is the only valuable species, but because the conditions evolved to favour its growth. Over time, the soil becomes impoverished and no longer accommodates species who can’t compete. Biodiversity declines and slower-growing species are crowded out. The ecosystem becomes highly productive in the short term, but fragile in the long term.

I wonder whether we have reached a tipping point, where we are at risk of something similar happening in the psychological field.

When a few highly organised, commercially fertilised platforms grow to a mega scale, they can inadvertently crowd out diversity, nuance, locality, cultural specificity, and the quieter forms of wisdom that do not scale easily. If we follow this trajectory to its logical endpoint, we find ourselves living in a world where the majority of accessible psychological knowledge is funnelled through a small number of high-profile individuals whose voices are amplified by large, well-marketed, and branded platforms.

In such conditions, it becomes much harder for local, community-based, culturally rooted, or experimental initiatives to take root. They often find themselves struggling for nutrients because the conditions of visibility, funding, and attention now overwhelmingly favour what has already scaled.

The field risks losing the very diversity that would allow it to adapt, regenerate, and respond creatively to the uncertainties of our time. The risk is that the field begins to imagine that psychological wisdom is what is offered through a narrow set of highly visible channels.

What’s at stake is not just the survival of smaller initiatives, but the richness of the psychological commons itself. In a world where our crises are profoundly local as well as global, we cannot afford a monoculture of meaning-making. We need a landscape in which many species of wisdom can grow.

Charismatic leaders

There is also the question of charismatic centrality. Much of the trust, visibility, and aspiration is built around the persona of one recognisable figure (who is still often white, male, middle class, and Western). This risks reproducing a hierarchical template that sits squarely within the logic of modernity, where knowledge, authority, and even spiritual legitimacy become subtly routed through a singular voice. Psychological understanding, which historically lived in diverse professional communities, lineages, cultural ceremonies, or rituals, has become organised as intellectual property with signature methods and protected curricula. Access increasingly comes through branded pathways, accreditation systems, and the endorsement of singular organisations.

Please note that this is not a call to dismantle high-quality professional training offers. They play an important role in maintaining quality and standards. Rather, I propose paying attention to what needs to be nurtured in addition, as the current structures increasingly reshape what younger practitioners aspire to. Instead of imagining a future rooted in local neighbourhood clinics, grassroots community initiatives, or locally situated practice, many now look to the global-brand model as the aspirational norm. ‘Success’ begins to mean scale, name recognition, slick production, and signature frameworks, rather than the long and hard graft of deep, grounded experience.

The sheer focus on scalability also has implications for what gets foregrounded. Content that fits well into the course-and-membership model gets amplified. Content that is hard to monetise at scale (like slow individual, communal, or institutional repair; community organising; political engagement; or culture-specific healing practices) receives far less attention. Systemic conditions risk being psychologised: the pain of living within extractive economies becomes framed primarily as personal or relational trauma to be attended to at an individual level, rather than as a mandate for collective structural change.

Access

Even with sincere efforts toward diversity, scholarships, and global access, these infrastructures are still shaped by Western models and paradigms, English-language dominance, and platform-based delivery. The result is that Western-centred frameworks become increasingly dominant and risk overshadowing the rich, place-based healing traditions that have supported communities for generations. Local modalities, rooted in land, lineage, culture, and community, can be subtly displaced by globalised approaches that travel more easily, scale more readily, and fit the aesthetics of a digital marketplace. In this way, diversity of practice can be eroded not by intention, but by the gravitational pull of a system that amplifies what is most portable, familiar, and marketable.

False narratives of competence and perfection

Another consequence of mega platforms is the emergence of the image of the impeccably curated public persona: the perfect teacher, the global expert whose image signals coherence, mastery, and transcendence. This creates the impression that some can have it all together while everyone else is perpetually catching up, learning, aspiring. The field becomes subtly divided into the enlightened expert and the listening and learning crowd.

Even if every effort is made to invite a diverse group of people into “expert” positions, the architecture itself leaves very little space for co-created knowledge. The hierarchy is implicit: there is a centre that teaches and a periphery that absorbs. It is a model exquisitely suited to modernity’s efficient, recognisable, marketable outlook, but it does not easily allow for collective authorship, shared inquiry, or the messy, emergent intelligence that arises only when many perspectives meet on level ground.

“Good enough” is not good enough

Who can afford to be pedantic, tired, grumpy, unsure, muddled, or a bit rubbish when the spotlight of a platform with tens of thousands of eyes is upon them?

The emphasis on personal brilliance and exceptionalism that is the main selling point of many large-scale platforms makes it incredibly difficult for anyone at the centre of these systems to show the parts of themselves that are ordinary, fallible, contradictory, or frankly not very likeable. In these conditions, teachers must appear endlessly regulated, endlessly compassionate, endlessly wise. The result is a culture that elevates the extraordinary and sidelines the ordinary.

And we have to ask: what are we doing when we remove the ordinary parts from view? What happens to our collective capacity to be with our own imperfections if the people we look to for psychological maturity cannot show theirs?

Winnicott’s notion of the “good enough parent” is one of the most liberating ideas in 20th-century psychology. Winnicott observed that when parents try to be perfect, or imagine they should be, it is actually harmful. His work emphasises that the good enough parent is not the flawless, endlessly attuned, emotionally immaculate figure that contemporary culture so often idealises. Quite the opposite. Good enough parenting is built on a rhythm of attunement and misattunement, rupture and repair, small failures followed by reconnection.

It is the ordinariness, the inevitable misunderstandings, the tiredness, the occasional sharpness of tone that allows a child to develop resilience, trust, and a sense of their own separateness. Perfection actually undermines development. It deprives the child of the necessary experience of surviving frustration and discovering that relationships can falter and come back together.

For Winnicott, this was the ground out of which the true self emerges. This is a self that can exist spontaneously, without performing and without having to meet an impossible standard. And this is precisely what becomes so constrained in a landscape dominated by highly polished personas and impeccably branded profiles.

When the people offering psychological and spiritual guidance cannot show their human fallibility and ordinariness, everyone else loses permission to inhabit theirs. The culture drifts toward a relentless but unachievable strive for perfectionism, an ‘as-if culture’ of shame and pretence that encourages narcissistic adaptations.

Winnicott reminds us that this is the opposite of what fosters psychological health. Real growth depends on the presence of people who are flawed, but ‘good enough’. The tolerance for ‘good enough’ is what makes maturation possible.

The marketing architecture

The new psychological and spiritual mega platforms operate with the full contemporary toolbox of the late-stage capitalist marketing culture of carefully optimised sales cycles. This keeps the lights on, pays salaries, and enables reach, but it also shapes psychological work to the rhythms of a highly commercialised culture with its perpetual visibility, attention economy, superlative claims, scarcity models, and overwhelming output of information. It fuels the hunger and keeps people returning for more.

Organisations trapped in a Double Bind

None of these unintended consequences negates the good that has also been offered. As outlined above, the rise of large players is a response to real longing, and many people have benefitted profoundly. Both gratitude and discernment are possible at once.

The more difficult question is: How do we cultivate the conditions that are necessary to nurture the rich diversity of a healthy ecology of the psychological commons?

I believe that this is the work of the next decade. We need to figure out how to rebalance the soil so that many forms of wisdom can flourish.

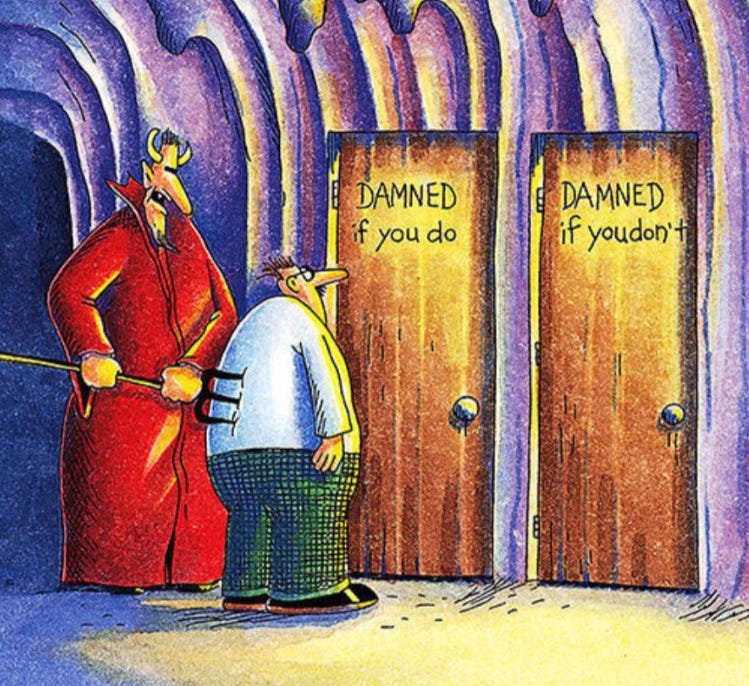

The conditions we all swim in place countless organisations in a painful double bind. If we adapt to the commercial logic outlined above, our diversity of approach risks being eroded. Over time, offerings become shaped by what is most marketable rather than what is most needed. If, on the other hand, we operate entirely outside of these forces, we risk invisibility and financial unsustainability, as the conditions overwhelmingly favour the existing model. And if we attempt to do both at once (to remain grounded in depth and integrity while also conforming to the demands of visibility and reach), we may find ourselves split between competing value systems, stretched thin, or diluted in our impact.

This is the paradox of the double bind we must learn to navigate. As I have written elsewhere, double binds are configurations in which every available option undermines some essential value elsewhere. Addressing a problem in one dimension results in a negative consequence or existential crisis in another dimension. Double binds cannot be resolved by choosing one side or the other. The only way through is to find a way of holding the tension without collapsing into either pole, whilst waiting for an opportunity to change the frame entirely.

For the Centre for Climate Psychology, this means acknowledging the very real possibility that we may not endure within this landscape. One’s own demise is certainly one possible way of transcending the stuckness within a double bind. I have written elsewhere that not all acorns are meant to become oak trees; some become mulch, humus, compost, and nutrients for others. We do not yet know what we will become, and there is humility in recognising that.

It is, however, also important to stress that double binds are not altogether negative. They offer an evolutionary dilemma to a stuck system. The tension they create also offers the opportunity for new emergence.

So I sit with the question of what a systemic response may look like. What adjacent possible action is an opening into new territory? What allows us to be in the world in a new way that does not try to solve the problem with the same logic and tools that maintain it? Below are some incomplete thoughts that may gesture in a new direction.

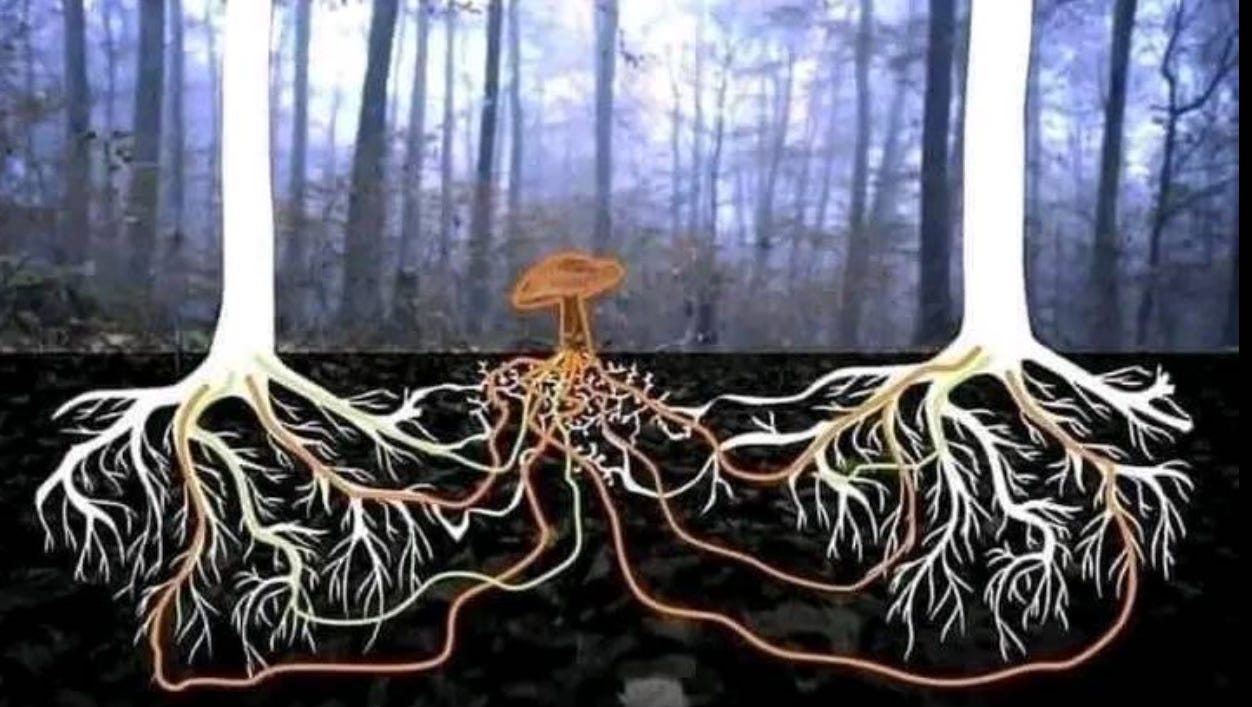

Mycelial Models: Redistributing Nutrients

In healthy ecological systems, the largest trees are connected by vast networks of fungal mycelium that move resources laterally, not just upward. The system survives because nutrients circulate.

Translated to our context, this would mean that it would benefit the ecosystem if large and established organisations redirected some of their resources to nurture small, experimental, local, culturally specific projects. This is not as a charitable act, but an ecological necessity that benefits the whole. This would entail a commitment to tend to partnerships that go beyond direct cost-benefit analysis, but that redirect visibility toward emerging voices, grassroots practitioners, and community-held knowledge.

1. Making Space for New Growth

Forests renew themselves when dead wood falls and creates gaps in the canopy. Light reaches the forest floor, and new species emerge. Without such gaps, regeneration stalls. Ecologically aligned organisations might make intentional space for others to rise, rather than filling every available niche themselves.

Organisations may create periods of non-production, where emerging practitioners are empowered to shape the field.

2. Diverse Root Systems: Knowledge Held in Many Places

In resilient ecosystems, adaptation, memory, and resilience are stored across multiple species and layers. When one species faces disease, others carry the thread of continuity.

An ecological organisation would therefore promote multiple lineages of understanding, rather than a handful of academic or branded frameworks. The creation of co-created knowledge spaces is important, so that the authority of expertise is not held by one voice alone, and power is shared and inquiry is collective.

Large organisations could support this by hosting dialogues between place-rooted lineages and cross-cultural knowledge exchange, and foregrounding forms of wisdom that resist commodification.

3. Avoiding Soil Exhaustion: Slowing Extraction and Restoring Ground

Industrial agriculture depletes soil by extracting more nutrients than it replenishes. The psychological field risks similar depletion when demand for content, insight, and “transformation” outpaces the human capacity to metabolise and integrate.

Ecological models would refrain from scarcity models and perpetual marketing and rebranding that give audiences the impression that they are in a constant self-improvement race. We need to slow down and take time to rest and integrate. This means supporting reflective, non-commercial spaces where nothing is sold, nothing is optimised, nothing is harvested for content.

4. Mutually Assured Flourishing: Stability Shared Across Sizes

In nature, ecosystems stabilise through interdependence. The large depend on the small as much as the small depend on the large.

Psychological ecosystems could mirror this by establishing consortia where large and small organisations collaborate, share infrastructure, technology, and resources.

A Closing Thought

Monocultures seem efficient; until the storm comes. They are high-yield but fragile. Diverse ecosystems, by contrast, look inefficient, slow, and tangled, as they learn together. They are, however, much more sustainable and extraordinarily resilient.

If the psychological field wants to play an active part in nurturing healthy cultures, we must find ways to transcend the double binds that we are all unintentionally entangled in.

Great piece Steffi , much needed. So much of what I do these days doesn’t even fit into definition of psychology, great to think of it as part of an ecosystemic diversification . So much of what you write here applies to very many fields and disciplines right now, vital reading, thank you 🙏

This is great Steffi - it puts into words a lot of issues I've been reflecting upon and grappling with for a while. Like noticing how the predominant voices on trauma psychology are white men, and wanting to learn more from other cultures and particularly marginalised people - many of whom know in an embodied, everyday reality sense, how to process trauma (collectively, as much as individually). And also often feeling the tension between claiming my feminist, decolonial approach to wellbeing whilst remaining a white, largely privileged woman with far greater influence and reach than many. Thank you for your suggestions on shifting these models we all feed into. My hope would be that any effort at 'collective' learning or including marginalised voices is not simply a tokenistic gesture - sadly we see a lot if this too in the mental health and wellbeing world. But your honesty around uncertainty and sustainability is refreshing and insightful.