Should I stay or should I go?

When Work Collides with Worldview: Value Conflicts and Double Binds in an Age of Collapse

‘This article first appeared in the April 2025 issue of BACP Workplace published by the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy. https://www.bacp.co.uk/bacp-journals/bacp-workplace/©BACP 2025.’

With the impacts of climate change hitting harder each year, employees are experiencing a sense of cognitive dissonance between the reality of the situation we’re facing, and the response from their employers. As growing numbers of people start to question whether their jobs make them complicit in the crisis, Steffi Bednarek and Matthew Green consider how we can help people to navigate workplace conflicts at such a critical time for our world

It’s an unwritten rule in the corporate world that you don’t talk about how you really feel about the climate crisis. The prospect of self-inflicted human extinction is hardly a topic for water cooler chat. And yet, with the global economic system still based on fossil fuels, growing numbers of employees are recognising that their companies are complicit in climate breakdown – whether they work directly for polluting industries, or the financial, advertising, insurance, accounting and other sectors that serve them.

Therapists and coaches may share their clients’ concerns, and find they too are working with and for businesses whose values don’t match their own. It’s a tension that can be hard to resolve – after all, how many of us can afford to hand in our notice in a cost-of-living crisis? The result is a collective muteness in the workplace that leaves feelings of fear, guilt, anger and shame with nowhere to land.

According to the UK’s Office for National Statistics, around three in four adults (74%) reported feeling (very or somewhat) worried about climate change.1 The concern can manifest in different ways: from gut-wrenching horror at witnessing climate disasters unfolding with ever-greater ferocity, to grief at the decimation of treasured habitats and the extinction of species, fears over the breakdown of food systems and societal collapse. Such anxiety can lead to disillusionment, burnout or moral injury, and may emerge in our therapy rooms, if our clients feel they are complicit in greenwashing campaigns or the perpetuation of unsustainable practices. Over time, these unresolved conflicts can lead to diminished mental health, strained interpersonal relationships, and a sense of disconnection from a person’s values.

Keen to respond, we created a space for professionals to safely explore their inner conflicts in relation to the climate crisis, inviting a degree of openness and authenticity that would be taboo in most offices. Our one-day seminar, called ‘Should I Stay or Should I Go?’ was attended by employees from sectors including finance, marketing, technology, philanthropy, public policy, and oil and gas.

Drawing on our combined skills and experience as a climate psychologist (Steffi) and journalist (Matthew), our intent was to address the need for collective processing, emotional validation and to provide practical strategies for navigating ethical dilemmas in the workplace. In this article, we share our learning in the hope that it may support and inform the way that therapists, coaches and HR professionals choose to work with clients who are facing similar ethical and moral dilemmas.

Unspoken truths

Feelings of isolation and frustration are common for employees who need to suppress what they are really feeling in relation to the climate crisis in order to get through another day at the office. Too often, it may not be possible to share concerns at home, with family or friends, which can compound the problem. We began by inviting participants to express their unspoken truths, with the intention of supporting the group to develop greater clarity about their dilemmas, and perhaps to identify new options for action.

While for some, that might translate into leaving a job that is no longer aligned with their values; for others, it could mean advocating for change from within their organisation. Often, it’s about realising that the right response is simply to maintain an open-ended inquiry, and be aware that it might take time to resolve. Our role as facilitators is to keep returning to what is known as the ‘zero point’ in Gestalt therapy – we have no investment in any particular outcome, but we support people to navigate the best possible options for themselves.

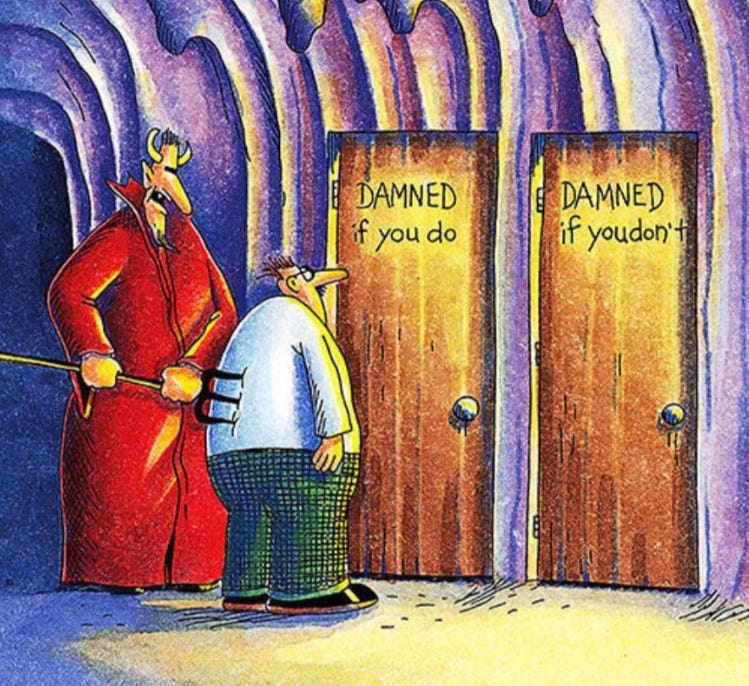

A double bind

We framed the central dilemma facing climate-conflicted professionals as a ‘double bind’ – a concept first introduced by Gregory Bateson. A double bind arises when individuals are confronted with contradictory imperatives that are impossible to resolve. For example, a career in the fossil fuel industry may provide financial security and a sense of professional identity. However, it also implicates the individual in practices that make the climate crisis worse, and in the enormous toll of death and suffering that entails. These kinds of climate double binds often lead to a sense of paralysis, guilt and complicity that can leave people more prone to depression, anxiety and burnout.3

Image By Gary Larson @1985 Farworks.Inc

Encouraging participants to explore their climate double binds, we drew on internal family systems (IFS) – a therapeutic model based on the idea that we’re all made up of many parts — ie sub-personalities who are constantly vying to control what we think, say and do. For example, our ‘manager’ parts are intent on keeping us safe by maintaining our standing in society, and playing by the rules at work. Unsurprisingly, our ‘managers’ are in a state of conflict with our ‘exiles’ – the disowned parts that carry feelings of doubt, shame and fear about our role in contributing to environmental collapse.

If we can learn to identify the different parts that are active in us, we can foster what IFS terms ‘self-leadership’. This means we can integrate the differing needs of our conflicted parts into wise action, learning how to overcome stuck patterns and navigate complex workplace dynamics in new ways.

The following case study with a senior fossil fuel executive named James (not his real name), shows how Steffi uses the IFS framework to support her coaching clients to confront their double binds.

Case study

Born into a wealthy family who values career, financial security and loyalty, James prided himself on his ability to provide a high standard of living to his wife and two children by rising up the ranks of the oil and gas industry.

However, headlines blaming his industry for climate disasters became harder to ignore. At home, James’ children started to question the source of their family’s wealth, expressing discomfort about his company’s role in the crisis they were learning about in school. What had seemed like a natural and fulfilling career path began to feel like a source of tension and unease.

James suppressed his discomfort by telling himself that he was just one among many working in his industry, and that change would come from within. But he was shocked when his daughter told him that she felt ashamed to say where her dad worked, and asked him directly: ‘Are we part of the problem?’ A week later, he attended a leadership seminar where an executive assured employees that their company was ‘a part of the solution’ to climate change. James knew that this narrative elegantly bypassed the damage that his company caused. He could see that the company’s concessions towards ‘sustainability’ were insignificant in comparison with the core impact of the business. As James became aware of this cognitive dissonance, the internal conflict between his values and professional identity deepened.

Using the IFS model, James identified his different ‘parts’ as: ‘the loyal provider’ who upholds family values; ‘the high achiever’ who needed success; and ‘the suppressed doubter’ who had carried guilt for years. Most poignantly, he connected with a part of himself he had long ignored — ‘the young idealist’, the boy who once loved nature, spent summers camping, and wanted to do good in the world. That boy had been buried beneath corporate ambition. It was his renewed connection with this part that guided James to eventually quit his job and join a renewable energy start-up. It wasn’t until he had left his old job that James realised just how heavily the burden of suppressed guilt had weighed.

Of course, his transition wasn’t easy — some belt-tightening was necessary, and James’ professional identity took time to reconfigure. But the new job brought James a sense of integrity that rippled through the whole family, and allowed him to employ his considerable skills on behalf of a cause he believed in.

(James is a composite character, based on real interactions and experiences from Steffi’s coaching work. Everything he expresses reflects genuine concerns clients have expressed)

From individual to the collective

Working with the whole group, we applied the IFS model, taking care to establish a sufficient sense of safety to explore dilemmas that might otherwise feel too uncomfortable or risky to voice. Drawing on the principles informing large-group processes to help integrate intergenerational and collective trauma,4 we used various check-in and introductory exercises to establish ‘coherence’ – evoking a sense of connection, relatedness and shared awareness in the group. This allows for ‘collective intelligence’ to start to flow, whereby individuals can access higher levels of insight, inspiration and understanding than they might if they were alone.

Participants found it helpful when Matthew shared his sometimes, painful experience of navigating a climate double bind while working as a journalist at Reuters news agency, and this served as an important catalyst for building coherence in the group.5 In response to Steffi’s questions, Matthew explained how initially he had hoped that his role as a Reuters climate correspondent would enable him to make a positive contribution but this gave way to a growing belief that his editors weren’t interested in hard-hitting climate accountability journalism. His suspicions that senior leadership was ambivalent about covering the climate crisis deepened when he later learned that the company’s events business was staging trade shows in Texas, explicitly designed to remove the ‘pain points’ holding back faster production of oil and gas . The company’s embrace of a deal to produce a sponsored podcast portraying Saudi Aramco, the world’s biggest oil company, as a pioneer of climate solutions further eroded his faith.6 Reuters says its events business ‘serves multiple professional audiences involved in the most important discussions of our day[SD3] ,’ and that the sponsored content running on its website is produced independently of the newsroom, and clearly labelled.

From loyal employee to whistleblower

Of course, in some cases, an employee does more than simply leave a role to escape their double bind – they seek to hold their former employer to account for the mismatch between its public commitment to tackling the climate crisis, and its actions. Matthew quit Reuters in April 2022 to work as an editor at DeSmog, a non-profit climate news service with a clear focus on holding polluters to account. He has since collaborated with leading climate journalist, Amy Westervelt of the podcast Drilled, to produce a report entitled Readers for Sale: the media’s role in climate delay, documenting fossil fuel sponsorship deals by major media brands including Reuters, The New York Times, Washington Post, and Politico.7 Breaking ranks with a professional tribe in this way is rarely easy – and may be catalysed by an event that makes the tension of the double bind impossible to tolerate.

This dynamic is starkly illustrated by the story of Lindsey Gulden, a climate and data scientist at US oil and gas major ExxonMobil.8

Lindsey spent more than a decade working for ExxonMobil until she was fired in 2020 for internally reportingan allegedly fraudulent overvaluation of company assets. (Lindsey is suing ExxonMobil for unlawful termination. The company denies fraud occurred and says her termination was unrelated).9

The experience prompted Lindsey to ask deeper questions about the oil and gas company’s assurances to staff that it is committed to playing a leading role in fighting the climate crisis – despite its tireless work to increase production of oil and gas.

At the Climate Consciousness Summit 2024, Lindsey said: ‘I truly, honestly believed — that because I was with good people, people that you trust your kids with, that everyone operating in ExxonMobil was working with the same concern for the environment, the same desire to tackle climate change. It is reasonable to assume that even though it’s not your job, someone, somewhere in the company is doing something, but in this case that’s just not true.’

‘Knowing what I do about the inside of the oil industry, knowing what I do about climate change, and the existential threat that it poses to us, to our children and to our grandchildren, I have much more responsibility than the average person to stand up and speak’.

While only a small minority of climate-conflicted employees may go on to become whistleblowers, we know there are many who can relate to the clash Lindsey experienced between her values and her professional duties. In her own practice, Steffi has observed how these unresolved conflicts can lead to diminished mental health, strained interpersonal relationships, and a sense of disconnection from cherished values.

Increasingly, professionals in a variety of sectors are struggling with the cognitive dissonance between wanting to make a positive impact and simultaneously being embedded in systems that undermine the planet’s future. Let’s take, for example, the advertising industry where creatives craft impactful campaigns for products with significant environmental footprints, or civil servants who experience deep despair when government climate policies fall short. Despite their awareness of these contradictions, they may find no viable alternative but to continue participating in these double binds.

Unconscious splitting

In this context, a psychological mechanism called ‘disavowal’ becomes a necessary adaptation. The psychoanalyst and writer Sally Weintrobe describes disavowal as an unconscious splitting between knowing and feeling that enables people to function within the status quo, while keeping the full implications of ecological collapse at arm’s length.11 Arguing that much of this disavowal is socially constructed, rooted in Western individualistic culture, Weintrobe notes how this mechanism supports emotional detachment from the consequences of the climate crisis – allowing individuals to acknowledge the terrifying facts of climate change without fully experiencing their emotional or moral weight. While disavowal may allow individuals to continue to function, it comes at a cost – depriving them not only of a felt-sense of the impacts of the climate crisis, but cutting them off from access to feeling in other domains of their lives as well.

Calls to action

So, what can we do? Noone can stand outside a system that currently brings unintended suffering to so many parts of life. But even for the most privileged, it’s not necessarily as easy as simply deciding to extricate ourselves from an entire line of work or industry. The bills need to be paid; the kids expect a certain kind of lifestyle. But what must we sacrifice to conform to these familiar patterns? Are there hidden costs that we would rather not acknowledge?

These questions live inside us but when people feel safe enough to express their fears, it becomes clear how climate change is so much more than an excess of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. It manifests in our personal lives – the aims and aspirations we pursue, the way we view ourselves and each other, the identities we build, and how we define success. It lives in the unseen, the things we no longer notice, in the banality of familiar daily rituals – from turning the ignition key in a car, to throwing away a plastic lid – that numb us to the damage they cause when practised on an industrial scale.

We hope this article will inspire other practitioners to consider how they might also help employees explore climate double binds – and find opportunities to work with their own responses to the crisis. The integrative psychotherapist Trudi Macagnino highlights how the social construction of silence around the climate crisis, in the therapeutic encounter, demonstrates that both therapists and clients are frequently defended against overwhelming feelings.12 But, therapists and coaches need to have worked through their own anxieties in order to support clients to face the state of the world.

There are ample opportunities for therapists and coaches to create spaces where clients feel safe exploring the intersections of career, values and their concerns about the climate crisis. For employers, the emphasis should be on fostering cultures of greater transparency and accountability that empower workers to voice their concerns without fear of reprisal.

Practical steps for therapists could include:

· Bring climate change into the room: We need to be prepared to do our own processing work around the climate and ecological crisis, and to understand our relationship with it and our defences. We need to learn to recognise the subtle cues from clients that may signal a preparedness to explore this collective problem, and be willing to support our clients to do so as well

· Seek community: The psychological impact of the climate crisis is too big for any individual to hold alone. Fortunately, there is now a growing ecosystem of organisations that recognise the importance of creating communities to support individuals to explore their responses. A few examples include the Centre for Climate Psychology; the Pocket Project; Grief Tending in Community; the Good Grief Network; and climate cafés offered by the Climate Psychology Alliance and other organisations

· Explore climate-focused professional bodies: Therapists working with climate-conflicted employees should be aware of the growing number of organisations that exist to support workers to initiate honest conversations about their organisation’s role in the climate crisis. Examples include Lawyers Are Responsible, Clean Creatives, Creatives for Climate and Culture Declares.

While our seminar allowed participants to reflect on their feelings of helplessness and anger, they also spoke of their desire to contribute meaningfully to solutions. Offering a facilitated space allows individuals to articulate their fears, connect with others, and begin to envision pathways forward — whether that means staying within their organisations to push for change or considering a transition to a new role. With support, people can find moral courage to do what they can to bring positive change into the part of the system that they are in contact with.

Closing thoughts

It’s just a few months since we held the seminar. Since then, the devastating fires in Los Angeles and the host of executive orders from US President Donald Trump, slashing environmental regulations and withdrawing from the Paris Agreement, have only served to underscore the enormous gulf between the world’s current trajectory and prospects for maintaining a liveable planet. But the climate crisis is not just a political and environmental issue — it is also a profound psychological and cultural challenge. By acknowledging the double binds that many workers face, therapists and coaches can help people give voice to their dilemma’s and the stuckness that prevents meaningful change.

We hope this article will support more practitioners to explore their own emotional response to the climate and ecological crisis, and – when they feel ready – begin to extend spaces for more people to do the same, in community.

Further resources

The Centre for Climate Psychology offers training and workshops for professionals to learn skills that support individuals and communities to navigate the complexities of the climate crisis with greater resilience and agency. Here you can find a resource page with videos explaining many of the concepts referred to in this article.

REFERENCES

1 Office for National Statistics. Worries about climate change, Great Britain: September to October 2022. [Online.] https://tinyurl.com/uhyj73cr (accessed 22 January 2025).

2 Bateson G. Steps to an ecology of mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1972.

3 Hübl T, Avritt J. Healing collective trauma. Boulder: Sounds True; 2020.

4 Resonant World. Processing my Reuters climate karma. [Online.] https://tinyurl. com/2raxee3r (accessed 13 February 2025).

5 Toxic Workplace Survival Guy. Why I went into exile. [Online.] https://tinyurl.com/2s3bcc3a (accessed 13 February 2025).

6 DeSmog. Reuters, New York Times top list of fossil fuel industry’s media enablers.[Online.] https://tinyurl.com/4sdac777 (accessed 13 February 2025).

7 Resonant World. Meeting my managers and exiles at our climate-conflicted workshop.[Online.] https://tinyurl.com/6w4x8a3v (accessed 15 February 2025).

8 DeSmog-Drilled. Readers for sale: the media’s role in climate delay. London: DeSmog-Drilled; 2023. https://tinyurl.com/bdz56yk9 (accessed February 2 2025).

9 Green M. Interview with Lindsey Gulden. [Interview.] Climate Consciousness Summit 2024, Pocket Project online conference; November 2024. https://tinyurl.com/326ffbkt

10 Green M. Q & A: how a former ExxonMobilemployee confronted the climate disinformation machine. DeSmog 2024; 7 November. https://tinyurl.com/2zbtuan5 (accessed 13 February 2023).

11 Weintrobe S. Engaging with climate change: psychoanalytic and interdisciplinary perspectives. Oxford: Routledge; 2013.

12 Bednarek S. Climate, psychology, and change: reimagining psychotherapy in an era of global disruption and climate anxiety. Berkeley:North Atlantic Books; 2024.

Bios

Steffi Bednarek is the founder and director of the Centre for Climate Psychology, and has over 25 years of expertise in training individuals and leadership teams in psychologically informed practices and complexity thinking. Her acclaimed book Climate, Psychology, and Change: new perspectives on psychology in an era of global disruption and climate anxiety has been celebrated as a work of wisdom and radical ideas. Steffi has worked for national governments, the corporate sector, global financial institutions, the sustainability sector and large NGOs.

Matthew Green is global investigations editor at DeSmog and creator of the Resonant World newsletter, serving the global trauma healing movement. His book Aftershock: fighting war, surviving trauma and finding peace, documents the struggles of British military veterans and their families to heal from the

This piece struck home. With a son in his 40s deeply depressed by the state of the world and pushed out of his creative directorships by AI, I feel his dilemma of needing meaningful work beyond minimal wage. He will never own a house. He will never earn enough now for a comfortable retirement. His trust in Global North governance and systems of 'care' is completely eroded. He sees what is happening. As a published and exhibited artist before 20, his lifelong dedication and extraordinary creativity, seems useless. Sensitive resonant artists, whom we need in this time, are often without activist communities and have no trust in pathologising mental health systems. Jeremy's work reveals his pain and wild sleeping rage that feeds his depression

This is important work. I already sense a need and an opportunity for a different kind of role for coaches and therapists. Thank you.